"More Than Mouse Catchers: The Mysterious Past of Cats"

From Perfume to Plague: There Were Cats.

Cats have long been seen as mysterious and independent creatures, often believed to have their own time to shine. Throughout historical literature, cats have been frequently mentioned, showing how popular and symbolic they were in earlier times.

In the Elizabethan era, cats were more than just skilled mouse catchers. They played roles in several industries, including medicine and perfume production. Apothecaries used substances related to cats in treatments, and their natural musk was valuable in fragrance making.

Because of their mysterious behaviour and piercing gaze, cats were often linked with superstitions. People believed they had magical or dark powers, leading to both fear and fascination. In extreme cases, cats were even used in warfare. Strategies included attaching flammable materials to them to spread fires during attacks.

These unusual roles show just how deeply cats were woven into different aspects of life during that period. From useful companions to misunderstood creatures, their history is filled with surprising and sometimes strange stories that reveal the complex relationship between humans and animals in early modern times.

Cats as perfumers :

Perfumers in the 17th century created many fragrances using extracts from civet cats. Despite their name, civet “cats” were actually closer to skunks, known for producing a powerful, musky scent that became highly valued in perfume making. The oily secretion taken from their anal glands was one of the most expensive ingredients of the time. Because this substance was naturally liquid, it was also easily blended into perfumes and even certain traditional or medicinal preparations.

The process of making perfume with civet cat musk begins with extracting the musk from the anal glands of the African civet cat. Traditionally, civets were kept in captivity, and their glands were scraped every few days to collect a thick, greasy secretion. This process was painful for the animal and could be fatal if repeated too often.

The raw secretion has a strong, unpleasant odor initially but is aged for several months to mellow into a sweet, musky scent. After aging, the musk is diluted in alcohol to create a tincture that can be easily blended into perfumes.

Perfumers add tiny amounts of civet tincture to fragrances, where it acts as a fixative, helping scents last longer, and as a base note that adds warmth and sensual depth.

Today, due to ethical concerns, most perfumers use synthetic civet instead, which mimics the natural scent without harming animals.

Cats against plague :

During the time of the Black Death in Europe, cats played an unexpected but vital role in controlling the spread of the plague. Since the disease was mainly carried by fleas living on rats, cats helped reduce the danger by hunting and eating these rats. However, people in the Middle Ages didn’t understand how the plague spread. Many believed that cats were somehow responsible for the disease itself. Out of fear and superstition, people began killing cats, thinking it would stop the plague.

This tragic misunderstanding had the opposite effect. Without cats to keep them in check, the rat population exploded. More rats meant more fleas carrying the deadly bacteria, and the plague spread faster and wider than ever before. Millions of people died across Europe as a result.

It wasn’t until the late 17th century, when the killing of cats stopped, that the natural balance began to return. Cats were once again able to hunt rats, and slowly, the number of plague cases decreased. This story serves as a reminder of how important animals are to ecosystems—and how ignorance and fear can worsen a crisis instead of solving it.

Cats as military weapon:

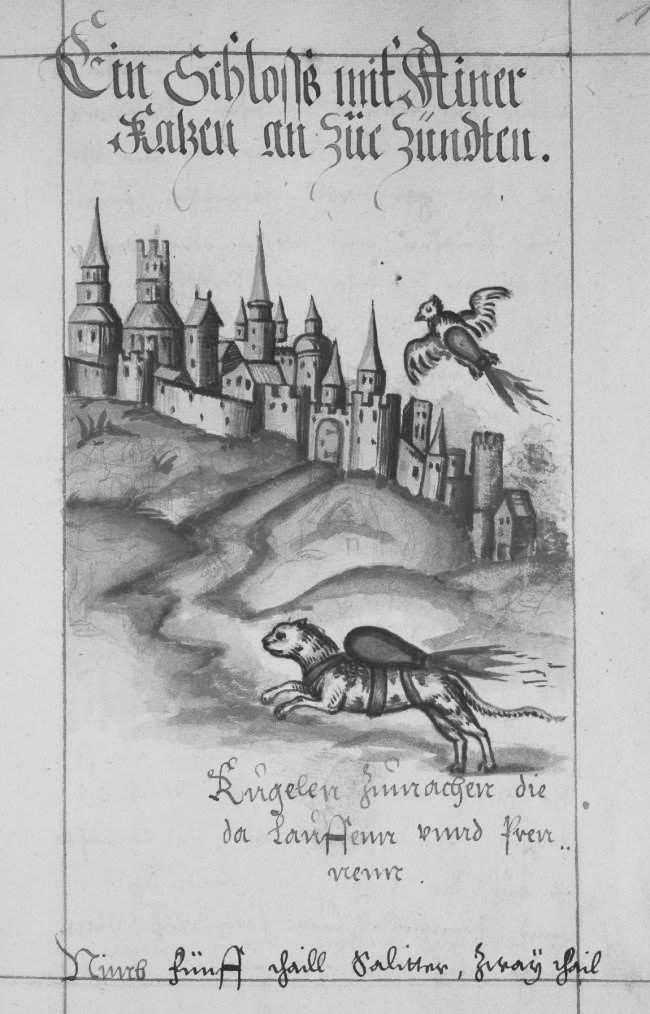

In medieval and early modern warfare, animals were sometimes abused as instruments of destruction. One notorious tactic—recorded in contemporary military manuals—described using terrified animals to start fires in besieged towns. The idea, attributed to artillery writer Franz Helm of Cologne, treated animals as unwitting incendiaries deployed to spread flames into buildings that were otherwise hard to reach. Manuals discussed exploiting an animal’s instinct to flee and hide in sheltered, combustible places so that blazes would ignite and grow beyond easy control.

This practice reflects a brutal realism in siegecraft: commanders sought any means to weaken defenders, and such suggestions show how desperation and cruelty could merge. Modern readers find these accounts shocking because they reveal deliberate harm to living creatures as a tactical option. Historians stress that while these methods were recorded, they were part of a grim catalogue of wartime ideas rather than widespread, routine operations.