"Innocence lost, lessons learned"

In the shadow of belief, innocence perished

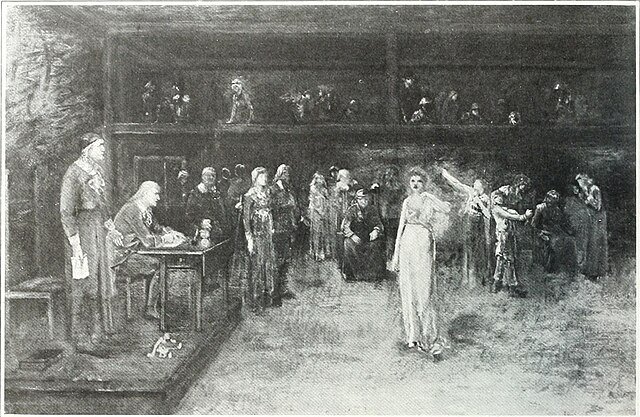

The infamous Salem witch trials began during the spring of 1692, after a group of young girls in Salem Village, Massachusetts, claimed to be possessed by the devil and accused several local women of witchcraft. The Salem Witch Trials one of the most haunting and well-documented episodes of mass hysteria in American history.

Since the 17th century, the story of the trials has become synonymous with paranoia and injustice. Fueled by xenophobia, religious extremism and long-brewing social tensions, the witch hunt continues to beguile the popular imagination more than 300 years later.

The trials occurred early in 1692 and mid 1693. The tragedy that unfolded during this short period revealed how fear and religious fanaticism could destroy lives and communities, leaving behind lessons that still resonate centuries later.

The Puritans of Massachusetts lived in a world governed by strict religious beliefs. They viewed the devil as a constant threat and believed that witchcraft was a real and dangerous crime. Life in the late 17th century was difficult—poor harvests, disease, conflicts with Native Americans, and political instability had created a deep sense of insecurity. Many people believed these troubles were signs of God’s anger or the devil’s influence. Against this tense backdrop, rumors of witchcraft easily found fertile ground.

Fear needed no proof

In January 1692, Parris’ daughter Elizabeth (or Betty), age 9, and niece Abigail Williams, age 11, started having “fits.” They screamed, threw things, uttered peculiar sounds and contorted themselves into strange positions. A local doctor blamed the supernatural. Another girl, 12-year-old Ann Putnam Jr., experienced similar episodes.

On February 29, under pressure from magistrates Jonathan Corwin and John Hathorne, colonial officials who tried local cases, the girls blamed three women for afflicting them: Tituba, a Caribbean woman enslaved by the Parris family; Sarah Good, a homeless beggar; and Sarah Osborne, an elderly impoverished woman.

All three women were brought before the local magistrates and interrogated for several days, starting on March 1, 1692. Osborne claimed innocence, as did Good. But Tituba confessed, “The devil came to me and bid me serve him.” She described elaborate images of black dogs, red cats, yellow birds and a “tall man with white hair” who wanted her to sign his book. She admitted that she’d signed the book and claimed there were several other witches looking to destroy the Puritans.

The Court That Listened to Spirits:

A special court known as “The Court of Oyer and Terminer” was established by Governor William Phips to handle the large number of cases. The judges, including Samuel Sewall, John Hathorne, and William Stoughton, relied heavily on “spectral evidence”—testimony that the spirit or shape of the accused had appeared to the victim in a vision. This type of evidence was impossible to prove or disprove, yet it became the main basis for conviction. Just a few days after the court was established, respected minister Cotton Mather wrote a letter imploring the court not to allow spectral evidence—testimony about dreams and visions. The court largely ignored this request, sentencing the hangings of five people in July, five more in August and eight in September. Cotton Mather said – “It were better that ten suspected witches should escape than one innocent person be condemned.” His words denounced the use of spectral evidence.

The Executions: