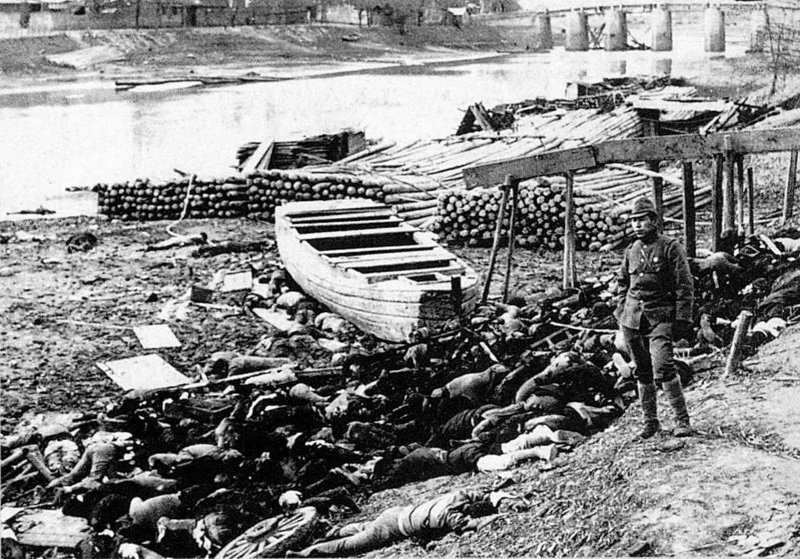

"The Day Mercy Died in Nanjing"

The Nanjing Massacre: A Dark Chapter in History

The Nanjing Massacre, also known as the Rape of Nanjing, was one of the most horrific atrocities of the Second Sino-Japanese War. It took place in December 1937, after the Japanese army captured Nanjing, then the capital of the Republic of China, following the Battle of Nanking.

In the weeks that followed, Imperial Japanese forces carried out mass killings and widespread sexual violence against Chinese civilians, noncombatants, and surrendered soldiers. The number of people killed is widely debated among historians, with estimates ranging from 100,000 to over 300,000. Reports also suggest that thousands of women—possibly up to 80,000—were raped during this period.

Despite variations in death toll estimates, there is broad agreement that the massacre was a grave violation of human rights. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East confirmed the crimes and held Japanese officials accountable after World War II.

The Fall of Nanjing and the Creation of the Safety Zone:

In the early years of World War II, during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese forces advanced rapidly through eastern China. After a brutal and costly victory in the Battle of Shanghai in late 1937, Japan turned its attention to Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China.

Faced with the threat of total defeat, Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek made the strategic decision to withdraw nearly all regular Chinese troops from Nanjing. The city’s defense was left in the hands of untrained and poorly equipped auxiliary units, who stood little chance against the advancing Imperial Japanese Army. Despite removing his forces, Chiang ordered that the city must be held “at all costs” and banned the official evacuation of civilians. While some residents fled in fear, many remained behind—unprotected and vulnerable.

As Japanese troops approached, a group of Western businessmen, missionaries, and diplomats formed the International Committee for the Nanjing Safety Zone. Their goal was to create a neutral area within the city to shelter civilians from the expected violence. Established in November 1937, the safety zone covered an area similar in size to New York’s Central Park and housed over a dozen makeshift refugee camps. On December 1, 1937, the Chinese government officially abandoned Nanjing, transferring responsibility for the city’s remaining population to the International Committee. All civilians still in the city were directed to relocate to the safety zone for their protection.

Unfortunately, when Japanese forces entered Nanjing on December 13, the safety zone could only offer limited protection. What followed was one of the most horrific events of the 20th century—the Nanjing Massacre, during which hundreds of thousands of civilians and prisoners of war were murdered, and tens of thousands of women were raped.

Japanese war crimes:

On November 23, Japanese forces committed a severe atrocity in the “Nanqiantou hamlet” (A small rural settlement in China).

“They set the village on fire, trapping many inhabitants inside. Soldiers repeatedly raped two women—a teenager and a pregnant woman. Subsequently, the teenager was brutally violated with a broom and bayoneted, while the pregnant woman was disemboweled, and her fetus removed. A two-year-old child was thrown into the flames, and his mother was bayoneted and discarded in a creek. The remaining thirty villagers were also bayoneted, disemboweled, and thrown into the creek, completing the massacre.”

A Japanese soldier describes a systematic and brutal routine used during the advance on Nanjing.

“The process began by separating the men from the women and children. The men were taken behind houses and executed with bayonets and knives.

The women and children were then locked in a single house, where the soldiers raped the women at night. The following morning, before the troops departed, they executed all the remaining women and children. To complete the destruction, they set fire to the entire village. The soldier notes that this final act of arson was intentional, ensuring that any survivors or returning residents would be left with no homes or shelter, thereby obliterating the community entirely.”

Unfolding the Aftermath: