“Where Courage Met Cruelty.”

A City’s Fall, A Nation’s Tragedy

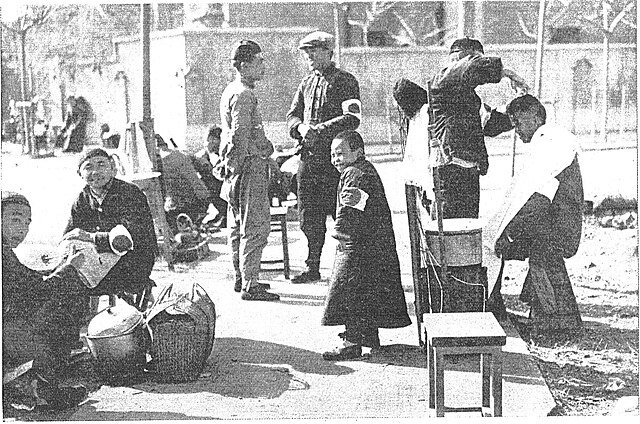

The Battle of Nanking took place in November 11 to December 13, 1937 during the Second Sino-Japanese War, shortly after the fall of Shanghai. It was a short but intense battle between the Imperial Japanese Army and the Chinese National Revolutionary Army. Nanking (now Nanjing), then the capital of China, was poorly defended after many Chinese troops had retreated. Despite limited resistance, Japanese forces captured the city on December 13, 1937.

Following the capture, the city witnessed one of the worst atrocities of the 20th century—the Nanjing Massacre. Over a period of six weeks, hundreds of thousands of civilians and surrendered soldiers were killed, and tens of thousands of women were raped.

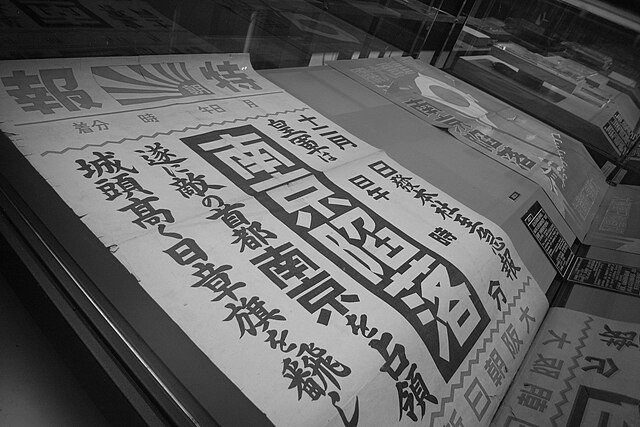

The battle and its aftermath shocked the world and severely damaged Japan’s international reputation. It remains a highly sensitive and painful chapter in Chinese history and continues to affect Sino-Japanese relations today.

Japan’s Intentions in the Second Sino-Japanese War:

During the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japan’s actions were driven by military ambition, economic interests, and imperial ideology. In the 1930s, Japan aimed to dominate East Asia, believing that controlling China was key to achieving this. China’s land, resources, and population made it highly valuable.

Japan promoted the idea of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, claiming to unite Asia under Japanese leadership. In reality, this meant Japanese control and exploitation of neighboring countries. Fearing Western influence, Japan sought to expand quickly before powers like the U.S. or Britain could interfere.

The 1937 war with China was intended to crush resistance and force China’s Nationalist government to surrender. Japan expected a swift victory, but underestimated Chinese resistance. Attacks on cities like Shanghai and Nanjing were part of a strategy to break morale and gain control.

Ultimately, Japan’s goals caused massive suffering and loss of life across Asia.

Breaking the Line: Japan’s Push to Nanjing:

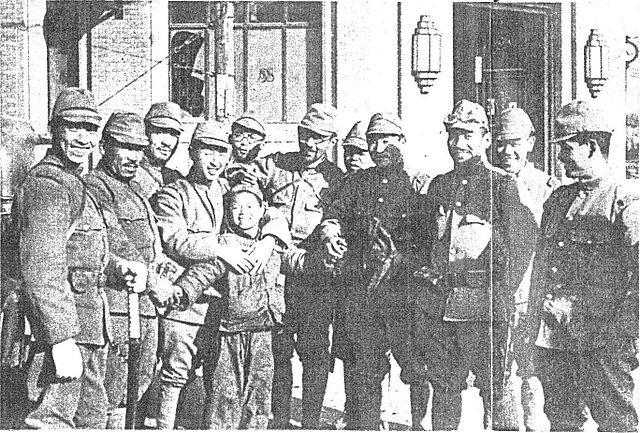

The Second Sino-Japanese War began on July 7, 1937, after a clash at Marco Polo Bridge escalated into full-scale conflict between Chinese and Japanese forces in northern China. To avoid a major confrontation there, China opened a second front in Shanghai. In response, Japan sent the Shanghai Expeditionary Army (SEA), led by General Iwane Matsui. Heavy fighting in Shanghai led Japan to send reinforcements, including the newly formed 10th Army under Lieutenant General Heisuke Yanagawa.

Although the 10th Army helped push Chinese forces out of Shanghai, Japan’s Army General Staff initially chose not to expand the war further. An “operation restriction line” was set to prevent forces from advancing west beyond Suzhou and Jiaxing.

However, both Matsui and Yanagawa strongly supported advancing to Nanjing, believing it would end the war quickly. Yanagawa violated orders and pushed toward Nanjing. Despite initial resistance, Matsui supported the move. Growing pressure within the Army General Staff led Deputy Chief Hayao Tada to remove the restriction line on November 24. By December 1, the operation to capture Nanjing was formally approved. At that point, Japanese forces were already advancing toward the city.

.jpg)

China’s forces:

The Nanjing Garrison Force was officially made up of thirteen divisions, including three German-trained elite units and the highly skilled Training Brigade. However, most of these troops were badly weakened from the earlier Battle of Shanghai. By the time they reached Nanjing, they were exhausted, under-equipped, and had suffered heavy losses. To rebuild these units, 16,000 young men and teenagers from Nanjing and nearby villages were quickly drafted.

The elite 36th, 87th, and 88th Divisions had lost many experienced soldiers and were now made up of about 50% new recruits. The city’s defenders also included units from Guangdong, Sichuan, and the Central Army, all of which had also suffered major losses. Some corps, like the 66th, were reduced to half their size and reorganized.

To reinforce the garrison, over 40,000 soldiers from additional battalions and regiments were brought in, along with 16,000 to 18,000 fresh troops from Hankou—most of them new recruits with only basic training. Due to the speed of the Japanese advance, many received minimal instruction before reaching the front lines.

Estimates of the garrison’s strength vary, but historian David Askew puts the number between 73,790 and 81,500, which aligns with Chinese officer records and other reliable sources.

Aftermath: